I stand with Philip Guston. But the art world has canceled him for four years.

The National Gallery of Art, the Tate Modern, and the Museums of Fine Art in Houston and Boston have jointly canceled their first-in-fifteen-years Guston retrospective with vague promises to reboot a commisar-approved, hand-sanitized version again in 2024.

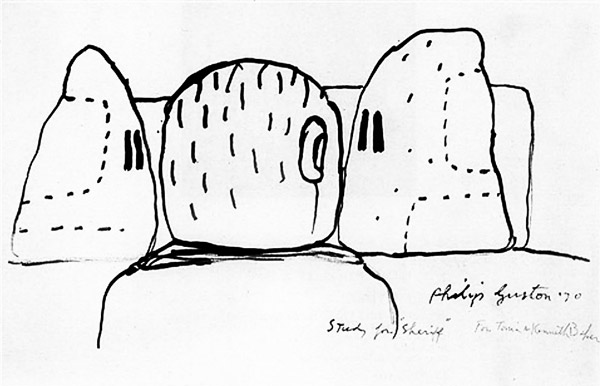

Philip Guston is one of the most important visual artists of the twentieth century, and among the most influential for the twenty-first. His career tracks the movement of modern art: from figuration to abstraction and back to figuration again. He developed a personal language for political forces, creating work that shattered the high-art edifice. The ridiculous pyramid heads, the 1930s cartoon eyes, the amorphous shapes—these were irresistible targets for him.

I went to art school during The Death of Painting (a proclamation of art history which cycles around every generation or so). Guston’s posthumous retrospective in 1980 resurrected the genre and inspired the Neo-Expressionist movement that dominated the decade. Though I have moved through abstraction and organic materials, I have settled to figuration—but a stripped down schematic of icons and symbols.

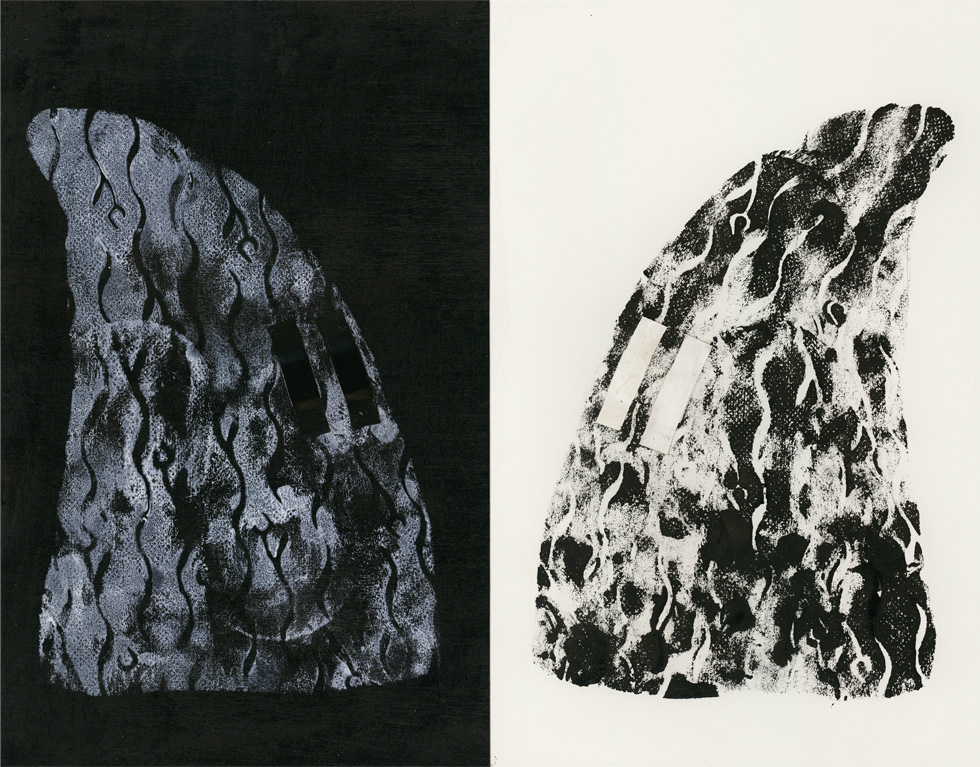

Another signature of his style is the meaty brushwork. The thick fleshy paint. In my own Klux series, I have remade Guston’s iconic image with Kotex and Band-Aids, using hands-free imprints of domestic and hygiene products to reinvent those incomparable brush strokes.

Band-aids and Unscented Kotex pantiliner imprints on paper

Lucy White